PETER DOIG

MICHAEL WERNER GALLERY, LONDON

19 DECEMBER, 2017 — 17 FEBRUARY, 2018

Peter Doig’s paintings often feel as if immediately behind their dream-like painted surfaces exists reality as we know it. This sense arises from a deliberate interplay between color, figuration, and abstraction, combined with multiple narratives and suggestible visual references, which gives rise to questions that, before they reach a resolution on the pictorial surface, are abruptly stopped by the physical limitations of the canvas, forcing the viewer to search within their reality for potential answers.

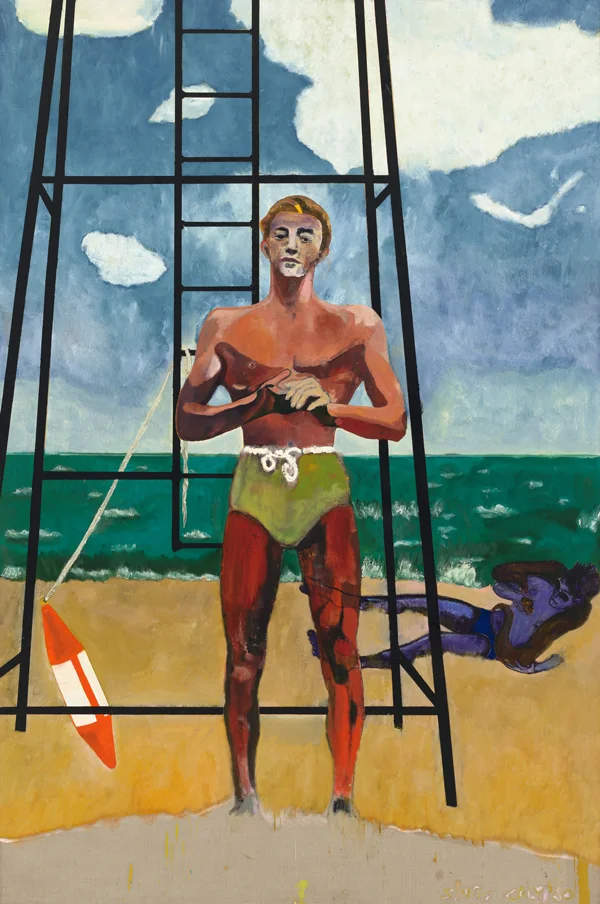

In Red Man (Sings Calypso) (2017), the title and references allude to questions regarding one’s profiteering through cultural spectacle. This in turn, evolves into the viewer questioning Doig’s authority and motives behind the creation of this work and his artistic practice. The painting depicts a rugged, heavily tanned man who wears green swimming trunks and stands on a beach. Behind him, to his left, is a lifeguard’s tower and, to his right, a figure rendered in dark blue hues, wrestling a snake. Although it is not explicitly stated where the man is, one can assume that he is in Trinidad, where Doig has lived since 2002, having also spent part of his childhood there between 1960 and 1966. This is given greater credence by the title, "red man” is a term commonly used by Trinidadians to describe both light-skinned mixed-race people and white people. Doig captures light with flicks of yellow in the man’s hair and a wash of white with minimal detail, showing that he is not a native of the island but also not immediately identifiable. The figure has his hands clasped in front of him, and, as the title suggests, is in the process of performing—or is about to start performing—a calypso, a genre of afro-Caribbean music that originated in Trinidad and Tobago.

Doig has since said that the man in the painting is Robert Mitchum, who shot two films and recorded an album of calypso music in Trinidad in the 1950s, an act of cultural appropriation through which he profited. But Doig also offers a counter argument—that of profiting through cultural spectacle—in the figure who wrestles the snake in the background. Dark blue rendering sets off a tension between the wrestler and the main figure by dividing the composition’s primary focal point. Docile snakes are often brought to Trinidadian beaches as a novelty item for tourists to pose with for photos. But the absence of an audience means that the viewer is maneuvered into this role for both figures, and at this point, the painting begins to gain traction beyond the composition. What is Doig’s role, as a white artist, in engineering this? What exactly are his motives for depicting such a scene? Are they valid, or is he exploiting a culture? Does his being raised there, albeit briefly, allow for this license to synthesize his observations and imagination, or are his paintings a form of appropriation?

This tension is perpetuated by a series of similar paintings, much smaller in scale, hung perpendicular to Red Man (Sings Calypso). They show similar figures at different times of the day and with various skin-tones. In Red Man (2017), the features of the face are obscured by blotches of dark brown with flecks of yellow and blue. The figure becomes something that can be embodied by the viewers, with their own experiences in such events drawn out. In Bather I (2017), the dark-orange sky and thick melee of sickly greens and moist browns that make up the ground is calculated yet loose. It gives a sense of entrapment to the figure caught in it, that is also addressed in Two Trees (2017).

In Two Trees (2017), Doig appears to place himself directly into the dialogue about his identity within the context of migrants. The sky is a pastel wash of purples and blues with a segment of ochre above a moon that rises over the faint, distant landmass of Africa. In the foreground, two dark-purple trees segment the work into three unequal sections, each inhabited by a figure. Their clothes are the primary focal point. They are explosions of vibrant colors painted with areas of slight impasto at odds with the calming pastel washes of the sky. In the far-left segment, a ghostly ice-hockey player wears a mustard-yellow jersey with a red, green, black, and white raised lattice of paint. This is an autobiographical element—Doig is an avid ice hockey player. In the middle, a dark-skinned figure wears a luminous white, knitted hat and a bold, baggy orange-red shirt with black and red stripped shorts. He stares towards the ground in front of the hockey player. In the far-right segment, another dark-skinned man in a loudly checked shirt, who is bald apart from a flick of hair tied in a ponytail on the top of his head, stands watching the other two figures through a handheld video camera. The hockey player is absolutely at odds with his surroundings. The kit suggests an archetype of western society, in particular North America and Canada (where Doig spent his adolescence), and the collision of these two elements brings to question not just identity in post-colonial Caribbean, but Doig’s identity as an immigrant in Trinidad. Doig puts forth that his everyday life is an omnipresent struggle. Given his background, perhaps he is seen through the lens of where he is from.

To expect Doig’s work to provide answers to complicated questions of post-colonial identity would be to miss the point. The uniquely compelling factor, which keeps the viewer in front of the works, is their lack of answers. In these paintings, more so than in any previous body of work, Doig directs the oneiric overtones from the present rather than from memory. As a result, the reflective concerns about place, identity, history, and the motives and authority behind Doig’s painting practice feel as if they reveal a picture of where Doig is at now.

First published by The Brooklyn Rail

https://brooklynrail.org/2018/03/artseen/PETER-DOIG

Peter Doig | Michael Werner Gallery, London

http://michaelwerner.com/exhibition/5025/information